St Andrews in the bush?

Chrissie Boughey (nee Williams) (MA, MA, DPhil) graduated from St Andrews in 1973. Her time at St Andrews as a ‘first generation’ student (made possible only by a government grant) led her to pursue the research interest that has sustained her academic career – the pursuit of social justice in higher education. It also allowed her to begin to understand some of the social and cultural barriers that prevent so many young people from accessing and succeeding in higher education.

Her early career was spent teaching English as a foreign language in places as diverse as Spain and Yemen. In the 1980s, she ended up working in South Africa thanks to a British Council funded aid project and, as the democratic election approached, decided to stay on to try to contribute to the new social order. She went on to complete a doctoral degree and establish herself as an academic and, for the last 21 years, has worked at Rhodes University in the Eastern Cape, where she now holds the status of professor emeritus. She compares the two universities here.

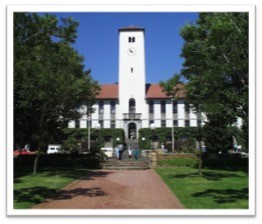

Rhodes University, like St Andrews, is located in a small, fairly remote town. Founded in 1904, its campus, arranged around quadrangles and lush lawns, as well as its academic practices, draws on the traditions of the ancient universities of Europe. It’s a small university, with about 8,500 students (one third of whom are postgraduate and about one fifth international) and is one of five or so ‘research intensive’ institutions in South Africa.

Little wonder, then, that when I first stepped on to the Rhodes campus in the mid 1990s, my first thought was ‘St Andrews in the bush!’ Thousands of miles away on a different continent, the University felt strangely familiar and, when I was offered a job there in 1999, I found it very easy to settle in.

Like St Andrews, the Rhodes University campus is now closed because of the COVID-19 crisis and teaching has moved online. However, coping with the impact of the virus is not the same in the Eastern Cape as it is in the East Neuk.

Until the early 2000s Rhodes University, although open to students of all social groups since the early 1990s, remained predominantly ‘white’ largely because its admission requirements excluded many black, working class students. Much of my work at the University, as Dean of Teaching and Learning and, later, Deputy Vice Chancellor, focused on strategies for ‘widening participation’. Nearly twenty years on, things have changed enormously with many students from very poor home backgrounds now funded by the government’s National Student Financial Aid Scheme (NSFAS) and coming from townships and rural areas across the country.

Although those on NSFAS funding receive free tuition and residence (or an allowance for living out as an ‘Oppidan’), the small book allowance paid annually will not cover the cost of a laptop computer. On campus, students have access to computer labs and computers in residences. Now that they have been sent home poorer students will, at best, have access to a smart phone and, thankfully, the telecommunications companies are providing free data for academic sites. This is of limited value, however, as many of these companies direct students to other resources such as YouTube videos, which require data to be paid for. You also can’t write much on a cell phone so ‘online learning’ is likely to be limited to viewing materials on the University’s online learning platform and taking part in quizzes and the occasional forum. More extensive forms of assessment that involve writing are not possible.

That’s not all, though. In my time at Rhodes, I became acutely aware of the guilt experienced by many students who ate three meals a day, slept in a single room in a residence and had access to running water and electricity when their families at home were living in miserable conditions, often funded only by granny’s state pension. As a result, some students chose to forgo the comfort of the residence system and move into digs in the township (often to their academic detriment) so they could send money home to their families. Everyone is now at home and the return of a student has meant an additional mouth to feed for many families already living on the breadline – even before the loss of employment resulting from the lockdown. The impact of watching loved ones suffer even more than they usually do is hardly conducive to study.

On 3 April I took part in an online meeting in my capacity as a member of a national Teaching & Learning Strategy Group hosted by the national Vice Chancellors’ Association. Some of the discussion in that meeting focused on whether or not 200,000 computers could be sourced to give to students. The sense was that getting hold of so many with the world in lockdown would not be easy. And even if we did get the computers, how many students would be reduced to selling them if their families were going hungry?

In the April St Andrews in the News newsletter, Claire Peddie, Vice Principal Education, told us in a piece entitled ‘Delivering against all odds’, that St Andrews has introduced ‘flexible and permissive options for progression and classification, as well as options for deferral and extensions’. Sadly, even institutional policy change may not make a difference to poor students here. Students supported by NSFAS are allowed four years of funding for undergraduate work, which means that they are able to take an additional year to complete a three-year degree if they fail courses. The vast majority of students need this additional year in the best of circumstances. Allowing more flexible progression options alongside deferrals and extensions may not actually help much in cases where students are already running out of funded time.

The same financial pressures will also apply to the group of students termed ‘the missing middle’ – the children of teachers, nurses and civil servants who are too ‘rich’ to qualify for NSFAS, who have no access to student loans and whose heavily burdened families have no collateral to offer banks. Many of this group also live in straitened circumstances and do not own laptop computers. An extension of learning time for these students, whose entire families scrape together their fees and living expenses month by month, will also be disastrous.

It’s hard not to wonder what will be left when the campus does open up again. How many of the undergraduates who, only a few short weeks ago, were greeting me as I walked across the lawns to my office, will be back? How many will only be back on a temporary basis, doomed to failure in the assessments that they will have to pass to continue with their academic careers – not because the University won’t permit them to continue but because they lack the funding that will allow them to do so? How many will be carrying the emotional and psychological scars of the losses they will experience and the scenes they will witness if the virus gets to rampage through the townships and rural areas?

As I get on with my research and postgraduate supervision by working from home (counting my blessings that I live in a house with a big garden with trees full of birds singing in the glorious autumn weather), I am sure of one thing: for poor students, the ‘odds’ are very different here in the Eastern Cape to what they are in the East Neuk.

In this time of crisis, this is no ‘St Andrews in the bush’.