Preparing for a Pandemic like COVID-19

Dr Gladys Kalema-Zikusoka is Founder and CEO of Conservation Through Public Health (CTPH) – the winner of the St Andrews Prize for the Environment 2020. Dr Kalema-Zikusoka is using the prize money to extend CTPH’s ‘one health’ conservation model (which has almost doubled the number of mountain gorillas in Uganda) to the Eastern lowland gorillas in neighbouring Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), whose numbers are reducing.

Here Dr Kalema-Zikusoka describes why she founded CTPH in 2003 and outlines the strategic programmes and structures that have brought the model both recognition and validation – in particular because of its positive management of COVID-19.

Background

We founded CTPH to prevent zoonotic diseases being transmitted between people and wildlife. While setting up the veterinary unit in the Uganda Wildlife Authority, I led a team to investigate the first scabies skin disease outbreaks in the then critically endangered mountain gorillas. The outbreak resulted in the death of an infant and sickness in the two gorilla groups that only recovered with Ivermectin treatment.

We discovered that the scabies came from people living around the park who had less-than-adequate access to basic health services, and I realised then that you cannot conserve the gorillas without also improving the health of the people with whom they share their fragile habitat.

Three strategic programmes

We developed three strategic, integrated programmes – the ‘one health’ model – to address this: community health, wildlife health and conservation, and alternative livelihoods.

Community health

With support from the Tusk Trust we built a Gorilla Health and Community Conservation Centre to regularly analyse samples from gorillas, people and livestock and so detect and prevent diseases that they could be sharing with each other.

Working with the Ministry of Health (MOH) and with support from the Whitley Fund for Nature we then created community conservation health workers who have become known as Village Health and Conservation Teams (VHCTs) since the Ministry of Health Village Health Team structure came to Bwindi. In addition to educating their communities about the importance of gorillas and the forest and how to prevent zoonotic diseases spreading between people and animals, the VHCTs also promote good hygiene and sanitation. This includes providing hand-washing tippy taps at every home and referring suspect cases of scabies, TB, HIV and other diseases to the nearest health centres. VHCTs also promote family planning, nutrition and sustainable agriculture to enable people to adequately look after their families.

Wildlife health and conservation

In addition, we train Gorilla Guardians who are community volunteers from the Human and Gorilla Conflict Resolution team to safely herd gorillas that forage in community land for banana plants and eucalyptus trees back to the national park. We also train the park rangers in gorilla health monitoring and how to manage tourists when they visit the gorillas to prevent a disruption in behavior and zoonotic disease transmission.

Alternative livelihoods

In 2016, CTPH started a Gorilla Conservation Coffee social enterprise to give farmers a steady market and above-market prices for good coffee, reducing their need to enter the park to look for food and fuel wood to feed their families. A donation from every coffee bag sold provides sustainable financing for community health, gorilla health and the CTPH conservation education programmes.

The coffee harvesting season begins in March and this year we felt compelled to continue buying the farmers’ coffee even if our main customers were no longer able to travel to Uganda as tourists. We were therefore delighted to be introduced to Moneyrow Beans – our first UK distributor – who wanted to buy premium and specialty coffee that would protect the gorillas. The coffee has been transported on cargo planes from Uganda and is now being sold in the UK, enabling people to support the gorillas without having to visit them.

The CTPH model and COVID-19

In 2010, CTPH joined the Ministry of Health (MOH) National Disease Taskforce, which brought zoonotic disease outbreaks – including Anthrax, Ebola and Marburg – under control, so we already had experience of dealing with such disease outbreaks when the first cases of COVID-19 were identified in Wuhan.

I travelled to St Andrews in late February 2020 with Alex Ngabirano, who is from the Bwindi local community and who has worked with CTPH for 12 years, ultimately rising to the rank of Bwindi Field Office Manager.

While Alex and I were at St Andrews University, I received an email from the wardens at Bwindi, asking us to support an initiative where tourists had to wear masks when visiting the mountain gorillas. CTPH and other conservation partners were already advocating this following research conducted by students from the University of Kent in Canterbury and from Ohio University in the US.

We left St Andrews at the end of February and, by the time the pandemic had reached Uganda in late March 2020, we had already jumped into action to prevent it spreading amongst people and from people to gorillas through the established structures that CTPH have been developing over the past 15 years.

Although Uganda had run out of surgical masks at the beginning of the pandemic, the COVID-19 National Disease taskforce advised CTPH that cloth masks with lining would work almost as well as surgical masks to prevent transmission from humans to the gorillas. All the conservation partners pitched in: local enterprise Ride 4 a Woman made cloth masks and the International Gorilla Conservation Programme bought them for our park staff; the Max Planck Institute donated surgical masks and the Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project and Bwindi Community Hospital provided technical expertise to train the park staff on how to prevent COVID-19 spreading from people to people and from people to gorillas.

CTPH also worked closely with the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) to train park staff to enforce the existing gorilla viewing rules of maintaining the seven-metre distance as well as the upgraded rules that include mandatory wearing of masks, taking of temperatures and hand washing and disinfection before visiting the gorillas.

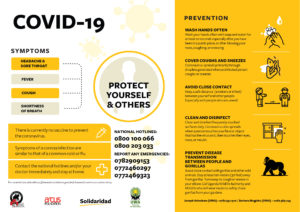

Finally, we developed posters with support from Solidaridad and with funding from the Arcus Foundation, as well as providing the same training to all our 270 VHCTs and 119 Gorilla Guardians, who also received cloth masks, soap, hand sanitizers and posters.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a suspension of primate tourism in Uganda to protect the great apes from human disease and to prevent spread of the virus among people. In the absence of gorilla tourism, the park staff still have to check on the gorillas every day to make sure that they are healthy and safe from poachers. With the loss of tourism, many people have lost an income, and this has driven them back to the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest to meet the needs of their families.

Unfortunately, this has led to the shocking and untimely death of Rafiki – the lead silverback of the Nkuringo gorilla group – in June, just two months after primate tourism was suspended. Rafiki was speared by a poacher who was checking on snares he had set for duiker and bush pigs to feed his family and sell in the local market. There has been no poaching of gorillas since 2011, when Mizano – a playful adult male blackback gorilla from Habinyanja gorilla group – was killed in the same way. The poacher who killed Rafiki came from Nteko parish where CTPH has set up programmes. This is leading us to intensify our efforts to bring benefits to all members of this Bwindi community.

Conclusion

The onset of the COVID-19 crisis has drawn attention to many of the key approaches and issues that we have been highlighting for years – including that of addressing the ‘one health’ interface between humans and wildlife. Our established CTPH programmes have already helped to mitigate the impact of the virus on endangered mountain gorillas and on the local communities with whom they share their fragile habitat. This in turn has helped to build a resilience in these communities to help them cope with COVID-19.

Post COVID-19, all the gorilla viewing regulations will continue to be enforced by UWA, and additional park staff are going to be trained. Furthermore, we are engaging people to go back to sustainable farming to support themselves and their families in the absence of tourism.

Thanks to the generous support from the St Andrews Prize for the Environment, all of these lessons will be transferred to build the same resilience in local communities where the eastern lowland gorillas are found, enabling a more secure future for both people and wildlife.

For more information about our work, please visit www.ctph.org and www.gccoffee.org.